A proportion of the differences that we observe between people can be attributed to their genetic differences. At the Hungry Mind Lab, we pioneer the use of DNA-based measures in research to predict people’s developmental differences. We are particularly interested in studying the interplay between genes and environments in children’s cognitive and social-emotional development.

Differences in children’s cognitive skills are apparent from as young as 2 years of age, and often increase over time from infancy and throughout childhood. To better understand why children differ so much in cognitive development, we conduct meta-analytic and original empirical studies. Our work on this topic is funded by the Nuffield Foundation and the Jacobs Foundation. Our findings will contribute to developing interventions that improve children’s cognitive skills and in turn reduce the gaps in school performance and educational achievement.

Our new report on the gene-environment interplay in early life cognitive development.

In May 2024, we completed a 4-year long research programme that involved data from 13,000 families, 8 core researchers, and countless collaborators and partners to better understand how genetics and environmental factors interact in children’s development during the early years. Our report summarises our research and explains our findings.

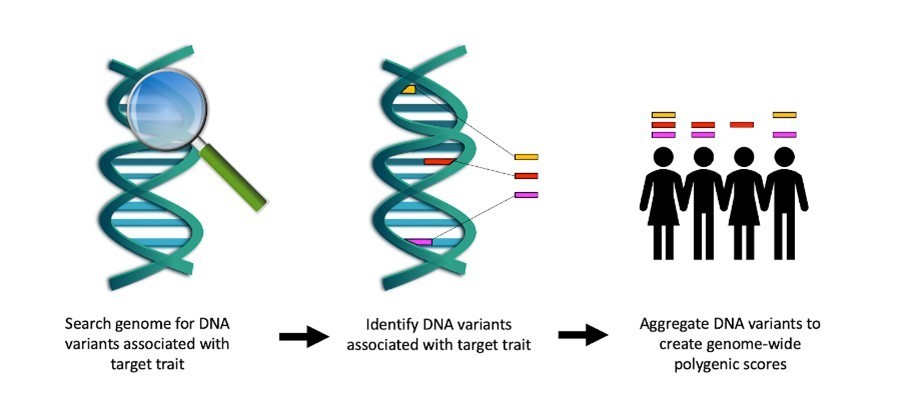

Polygenic scores are based on genome-wide association studies, known as GWAS, which search people’s genomes for tiny differences in DNA variants. GWAS look for DNA variants that occur more often in people with a particular trait than in those who don’t show the trait. One or two of these DNA variants alone will explain very little of people’s differences in traits because individual DNA variant’s effect sizes are tiny. In fact, genome-wide association studies or GWAS have shown that people’s differences in traits related to cognitive skills are due to many thousands of DNA variants. Once we know from a GWAS which DNA variants are associated with a trait, we can analyse people’s DNA and see how many of those DNA variants they carry. We can then aggregate a person’s DNA variants, and this aggregate is known as polygenic score, which indexes the person’s genetic propensity for a trait or behaviour.

In short, polygenic scores can capture a person’s genetic propensity for traits, such as cognitive skills. Because people’s differences in cognitive skills are at least partly heritable, polygenic scores are good predictors of a person’s cognitive skills.

An increasing number of research studies use polygenic scores to predict psychological traits, medical disorders, and psychiatric diagnoses. In our studies, we have used polygenic scores to predict children’s differences in school performance, reading ability, and social-emotional development.

We have made a series of videos to explain how genetic influences affect our traits and behaviours.